Audio Acronyms: DCA, VCA, Groups, and why the nuances matter

TL;DR:

A look into DCAs and VCAs – seemingly strange and esoteric acronyms – how they can help you mix, and how they differ from groups.

The Story:

As audio mixers got bigger, it made sense to have the controls for outputs, submixes, and other master knobs and faders in the center of the desk. One of the brilliant inventions of the analog era was the VCA – which stood for “Voltage Control Amplifier.”

The way to look at a VCA is as a remote control. It allows you to group faders together, without having to hunt around the board or grow extra hands.

From one of my favorite resources, Soundonsound.com:

“In a large–format analog mixer, a VCA, or Voltage Controlled Amplifier, is a channel gain control that can be adjusted by varying a DC voltage on the control input. This makes it possible to ‘move’ a raft of faders together, maintaining any offsets within them, by moving a single control fader.”

As digital boards came into being, that usability and workflow was desired by engineers, and so the DCA was born. It basically does the same thing, only digitally, not via voltage.

Groups, on the other hand, allow you to bus channels together – which might be for more than just volume control, since you can add effects.

Let’s look at how you might want to use these, and compare them.

The Esoteric Bit:

First off, I’m not going to tell you how to assign DCAs, VCAs, or groups – every board is different. and may have variations in the implications. We will proceed with general terms, with some specific examples. I am also, for this article, using DCA to mean both DCA or VCA – they do the same thing, and DCA is more modern. We will assume you have 8 of them, since that’s a common number. Also, while I use the term “group,” some manufacturers may refer to these as subgroups, mixes, busses, or a number of other terms, which may have their own implications.

First, an easy example. At NVCC, our main stage rep plot is mostly used for the lectures and dance groups that come in. The plot features a pair of podium-mounted mics, three wireless handheld/lav combos, a DI from the board, and a DI from the booth. We also have a bunch of other stuff plugged in – the rest of the wireless rack, a CD player that’s seldom used, etc.

Because of how the channels are set up, the channels we most often use are spread across two pages on our Midas M32. To make mixing easier, I’ve assigned all of these channels to DCAs, so that everything can be mixed with the 8 faders on the DCA page – no flipping back and forth between the podium mics on channels 1 & 2 and the laptop DI coming from the stage on channels 31 & 32.

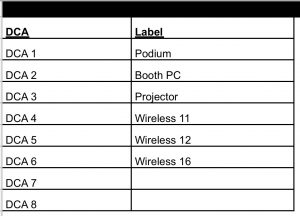

The DCA assignments look like this:

Just hold the select button on the DCA in question, and press the select button to light up the channels you want controlled by that DCA. Makes things rather easy. Set your levels, and then ride the DCAs to mix.

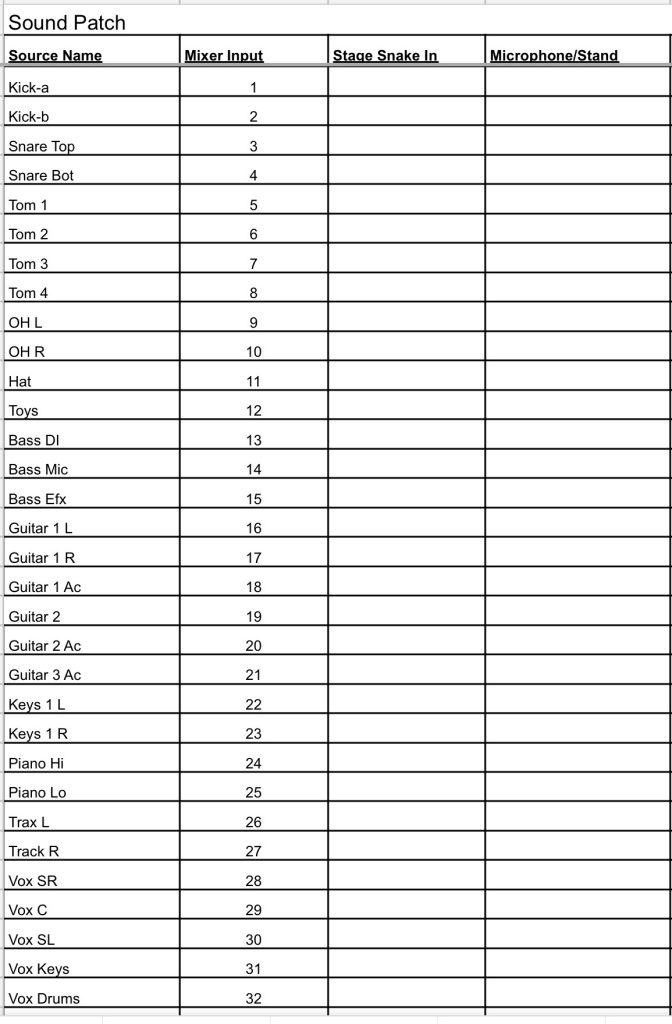

Now for something more complex. Let’s say you are mixing a rock band. There might be 12 channels of drums, three for bass (DI, effects, & mic), 6 for acoustic and electric guitars, 6 for keys and sampler, and 5 vocals channels – and don’t forget a few effects returns! Your patch sheet would look something like this:

(You ARE making patch sheets, right?!)

Depending on the band and your style, you may want to approach organizing and layering your mix in a few different ways, once you have all of your inputs and levels set. Obviously, when you are live mixing something like this you only have so many fingers and want to control fewer faders in mixing. All of the drums may sound great by themselves, but pulling back 12 faders of drums that are too loud in the mix starts to destroy the balance you worked so hard on. Similarly, the vocals are blending nicely, but when the song heats up and you have to boost the lead vocal in the choruses, you don’t want to suddenly leave the backing vocals behind when they come in.

In these cases, grouping your channels together with a DCAs or groups helps alleviate the situation. Putting all of those drums into a group, or controlling them with a DCA, would mean that a single fader would allow you to control the level, instead of 12 faders (discounting that things like overheads and top/bottom snare might be paired).

So which do you use? Here’s where “it depends” comes in. You might want to control your 4 backing vocals on DCA 6, with DCA 7 as your lead vocal (independent control, but next to each other, with the lead first so that you don’t have to quickly find the “center vox” etc. Maybe DCA 2 is for all of those Bass channels. And so on. (It may seem like I skipped straight to random numbers, but I organize my mix similarly throughout the whole board – drums first, then bass, guitars, keys, other stuff, vocals, and effects.)

For those dozen drum channels, you could route them into a stereo group (and not to the main mix) instead of using a DCA. Sure a DCA would work for level control, but here is one of the big differences between groups and DCA control: you can apply effects to a group. Putting a final EQ and Compression on that stereo drum group could help glue those 12 mics together better, for a more cohesive sound. Here you would use a stereo group (or two groups that are paired and linked as stereo), so as to keep the panning of your input channels intact.

A DCA is basically like a remote control – you can’t put effects on it or route it.

From there, you could, on most boards, assign that stereo group to DCA 1 if you wanted, thereby putting your top level of control next to everything else. (See, then Bass is DCA 2…)

During the show, you could always go back to your channels and pull back the snare top but boost tom 2, because that’s how the drummer is playing. But your overall control setup means you are dealing with fewer faders for the overall mix, and less paging on a digital desk – or reaching, on an analog one.

Back in the analog-only days, groups also made it possible to apply effects more easily – that big outboard rack might have a lot of compressors, but they get used up quickly in an environment like this, or you only have so many channels of a certain kind of compressor. So maybe your kick and snare got dedicated compressors, but the four toms got lumped together into two channels, via a group.

In the digital era, you are only limited by your imagination. You can turn on compression to every single channel, whether it needs it or not. A lot less planning of resources can be involved (see my note below). However, perhaps routing through groups can save you time, using the analog method. Mixing a cattle call show in a club with five bands, you might want a group for guitars, just so you can compress all of them and their myriad of sounds, without dialing in each and every player, during each 15-minute changeover, because you have no idea of what to expect.

NOTE: You should keep in mind that digital mixers ARE computers. We have all seen what happens when we ask our computer to do too many things at once. Things slow down. They aren’t as efficient. So, while in realistic use you probably won’t run into bottlenecks, you might want to not turn on Every. Single. Effect for all your channels if you don’t need them. In some cases, it may just throw an error and say you are out of plugin channels or something like that.

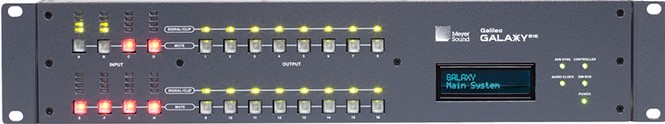

This is also why on bigger systems we often have outboard gear (which can still be digital) handling things like complex routing and effects like system EQ and delay alignment, allowing the mixer to just focus on inputs.

Next week, I am going to go into my own band mixing philosophy, using groups, DCAs, and parallel compression.

Cheers!

-brian

PS: I have come to embrace the digital revolution in mixing. Like it’s studio counterpart, the change in tools has changed how we mix, and ultimately how we listen to and experience music.

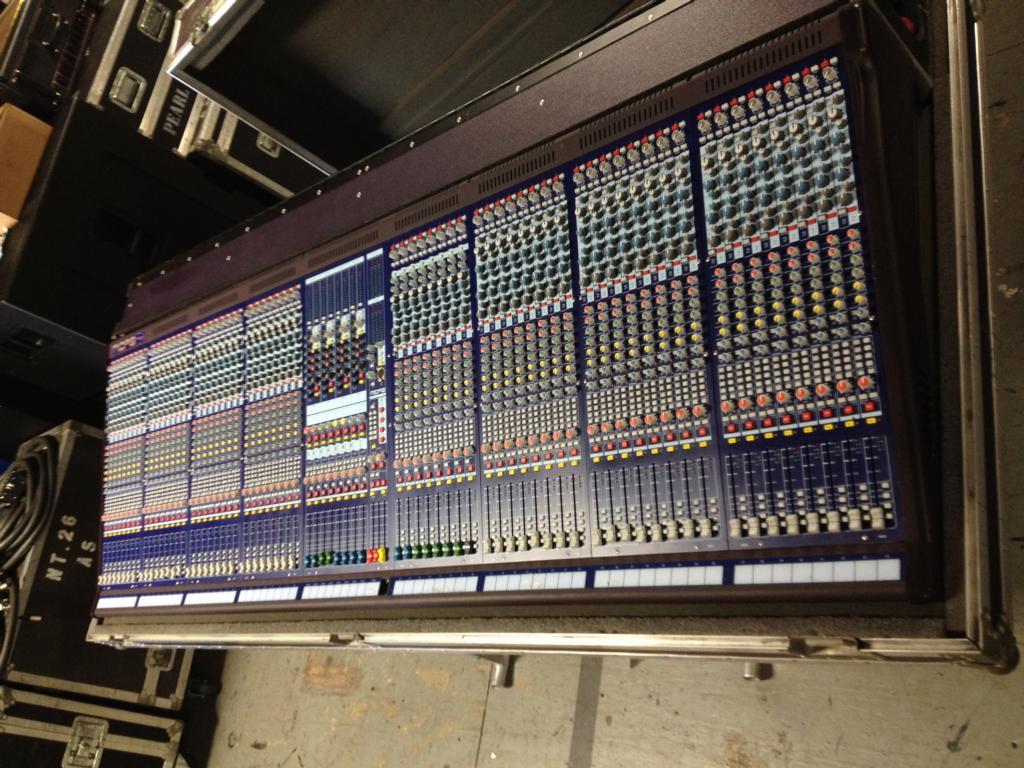

But however much I love certain digital mixers for different gigs, I get a rush every time I have to go into a full-analog environment (which is well-maintained). You really have to think about your resources and how the sound is getting from the stage, to the FoH, and back to the stacks.

For you younger engineers who may not have had the luxury of mixing in a proper analog venue, I recommend it. It really gives you a better appreciation of our modern tools, and it’s a lot of fun.

But don’t forget your paper, pens, and extra board tape!